How digital platforms are reshaping our cities

15 March 2021

Törnberg knows from personal experience about the consequences that platforms like Airbnb can have: he was evicted from the apartment in New York where he completed his thesis because the owner wanted to rent out the house through Airbnb since that would make him much more money.

But the platforms not only have an economic impact, their algorithms and interfaces are also reshaping how we experience cities, how think about them and how we imagine them.

What exactly are you going to research?

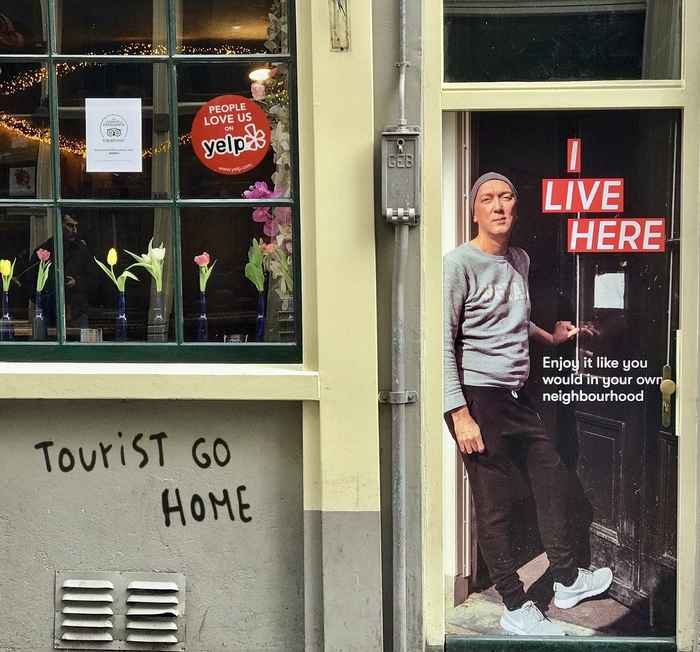

‘I study how cities are portrayed in reviews, posts and descriptions on digital platforms such as Airbnb, Yelp and TripAdvisor, and how these representations are reflected in the city and affect urban life. Platforms have their own logic; because of their design and algorithms, certain forms of content tend to become more visible. Consider Instagram, for example: the images that work well are eye-catching, colourful, and simple enough to work on a small screen. This logic leaks into the city, as restaurants, cafes or museums try to become more visible on the platforms. In a way, the cities have become partly digital. This can be seen in, for example, cafes in Amsterdam that have created decorative walls displaying bicycles, quotes or hashtags for people to use as backgrounds for their selfies. This example is fairly harmless, but digital culture can also have more serious consequences – it can become part of the dynamics of phenomena like gentrification and overtourism. It can even lead to conflicts over the right to define an urban place.‘

What do you mean by this can lead to conflict?

‘Because the platforms are driven by economic interests, they promote certain ways of interacting with the city, emphasising a consumption-oriented or what we might call a touristic relationship with the city. And this can affect other ways of relating to the city. Airbnb is selling, as they say in their slogan, the ability to “belong anywhere” – but the question is how this affects others' sense of belonging.’

Airbnb is selling, as they say in their slogan, the ability to “belong anywhere” – but the question is how this affects others' sense of belonging

Do you have any concrete examples of this?

‘Take the Corinthian Baptist Church in Harlem, New York. This church has served a local African-American congregation for decades. But a few years ago, churchgoers noticed a shift: more and more white visitors were coming to the church services. But they weren't there to pray: they had cameras and selfie sticks with them. The church had suddenly become a tourist destination. What had happened was that the church had been “discovered” on review websites such as Yelp and TripAdvisor, and had begun to rise in several lists of the “top tourist sites of the city”. The tourists flocked to experience what some reviews described as an “authentic experience of black culture”, and others as just a “free concert”. Many of the congregation members felt uncomfortable, and no longer at home in their church, because their personal worship and prayers were being filmed by tourists. This illustrates how platforms can cause conflicts over the right to an urban place.‘

How will you investigate this influence?

‘I am adapting recent methods in natural language processing to use geographically localised text data. This allows me to study how geographic space is represented in millions of reviews and posts, creating a map of the cultural representation of a city. Using these methods, I can see how the representation of neighbourhoods changes as the neighbourhood gentrifies, for example. I will use this as part of a critical and interpretive approach to studying the cultures of cities. In doing so, I am focusing on Rio de Janeiro, Amsterdam and New York.’

What can policymakers do with your research?

‘The impact of these platforms is something that really occupies policymakers, not least here in Amsterdam. The municipality of Amsterdam grapples quite openly with the image people have of the city and what kind of visitors it attracts. I hope to contribute to a better understanding of how platforms are part of shaping this image, and will provide tools to get hard data on how the city and its neighbourhoods are represented, and how this representation is changing. These tools and data will be made available on the project website, DigitalUrbanCulture.com.