The internet is headed for a ‘point of no return’ where the disadvantages will become too great

17 november 2022

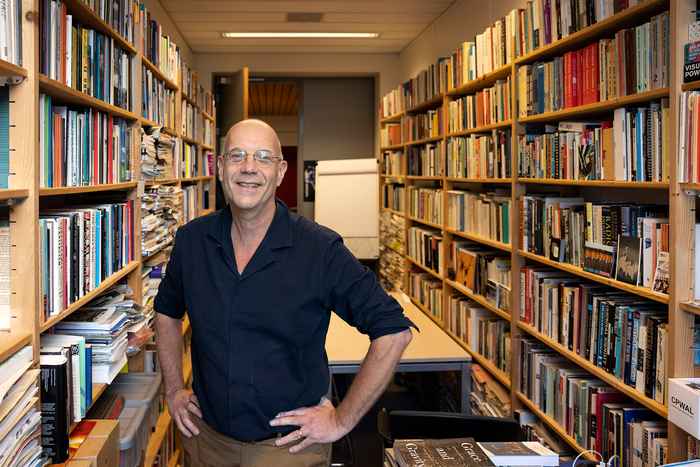

Lovink has always remained a public figure as an internet pioneer for his involvement with The Digital City, a precursor to the internet. Its founders envisioned it becoming a decentralised network, maintained by citizens, for citizens. ‘We lost that battle in spectacular fashion,’ Lovink sums up. The fact of the matter is that the internet and addictive apps are in the hands of Big Tech, which cares little for individual rights or society as a whole.

In his essay, Lovink shares insights gained from 30 years of critiquing the internet and researching counterculture, a time in which he has worked with art historians, artists, creative researchers and meme makers. He has researched Wikipedia, search engines, social media and cryptocurrencies and their profit models – always from the perspective that the internet is broken, but can and must be fixed (as also argued by Waag founder Marleen Stikker in her book).

Beyond repair?

In the past six months, however, Lovink has begun to change his mind. Can the internet, in fact, be fixed? ‘There may come a point when that’s no longer possible, after which time the adverse consequences can no longer be controlled. The internet is headed for a point of no return, and Big Tech is probably already aware of this, too. Mark Zuckerberg has moved away from his social media platforms and launched Meta, as if nothing’s wrong and we can just start over again, but it’s clearly already broken.’

Opinions have consequences

Lovink sees this point of no return approaching because now even ‘ordinary’ users increasingly have to pay a price for our far-reaching dependence on the internet and addiction to social media and apps. ‘This price is first of all psychological. Not only are a lot of young people suffering from a distorted self-image and anxiety disorders, there’s also been an externalisation of functions: certain critical functions of our brains are being outsourced. Our short-term memory is getting worse, and our attention is becoming increasingly fragmented and very specifically directed.’

At the same time, social control is increasing and users are being closely monitored. ‘Our supposed freedom of expression no longer actually exists,’ Lovink asserts. Consequences for those who share non-mainstream opinions online, for example with respect to their job or circle of friends, have now reached the Netherlands as well. ‘We’re already beginning to see indications that people are posting their opinions less and less.’

Repercussions are also to be expected here as control becomes increasingly more sophisticated. ‘In China, it’s already the case that you can’t board a train if you have a “wrong” opinion. In the United States, you have to share all of your social media profiles if you want to apply for a visa. Things don’t seem to be so bad in western Europe yet, but your online activity is so traceable and visible now that there’s a real possibility that at a certain point people will no longer be able to travel or get a mortgage or insurance.’

This sophisticated control will eventually become so pervasive, even here in the Netherlands, that people will ultimately turn away from the internet, Lovink thinks. ‘I believe that people will begin to shun technology.’ He draws a parallel with the climate crisis: ‘The climate emergencies have reached a point that’s beyond repair. People have begun to mobilise en masse because individual actions like installing solar panels are no longer enough.’

Extinction Internet

If we look a bit further ahead, things become even more dramatic. Lovink sketches a scenario he refers to as ‘Extinction Internet’. That might sound like we will all become extinct, but that is not what he means. However, he does envision a future in which certain services will no longer be available – also in light of the geopolitical situation and the climate crisis – and this will in turn lead to reduced access to or disconnection from the internet.

The idea of losing connection to the internet might seem inconceivable, especially to young people, but it is necessary that we take a critical look at the future. ‘A year ago the prospect of being without gas was unimaginable, and yet that’s now a distinct possibility given the situation with Russia. In the same way, given the climate emergencies, it’s also possible that the necessary infrastructure, such as electricity, will fail and the internet will go down along with it. With the entire population dependent on it, the likes of Elon Musk are bound to come along to offer a very expensive and exclusive satellite connection.’

Weaning ourselves off internet dependency

While this will have drastic consequences, Lovink believes that we can ultimately free ourselves from the clutches of the internet. ‘I think it’s possible for us to wean ourselves off it. Different software or other constructs could arise that make us less dependent. It’s good to reconsider the argument for efficiency. How important is it to us for all bridges to be controlled remotely? Why do bridge operator stations need to be converted into hotel rooms? What is the argument for this new efficiency? And how convincing is it?’

The Netherlands in the clutches of big corporations

Although many other countries still see the Netherlands as a free port, our country is in fact completely controlled by big corporations. Lovink: ‘And we’re proud of it, too. Recently, however, we seem to have reached a turning point, when the big data centre proposed in Zeewolde was rejected. Residents rightly asked the question: why should we want to use our green energy to power Facebook’s data centre? At a certain point, the corporate argument is no longer convincing. The question we ultimately have to ask our government is: why have you made yourselves so dependent? And can you still sell this to us as progress?’