A smarter way of dealing with green hydrogen uncertainty

14 januari 2026

The Netherlands is particularly important for the use of hydrogen, says Starreveld. ‘There's high energy demand in sectors like aviation and heavy industry. We have extensive natural gas infrastructure that can be reused for hydrogen transport and storage. And we have access to offshore wind energy, which allows for the production of green hydrogen.’

But many questions remain unanswered: Is hydrogen truly an affordable way to make industry more sustainable? Is it smarter to adapt existing natural gas pipelines or to build new ones? And what will large-scale offshore green hydrogen production actually cost?

Calculating thousands of possible futures

‘Mathematical optimisation is a way to use calculations to identify the best choice in these kinds of situations,’ Starreveld explains. ‘You transform the problem into a model with choices, a goal and constraints. Then an algorithm calculates which decisions are optimal.’

Together with other researchers from the UvA, as well as Delft University of Technology and business representatives, Starreveld developed a method that doesn't rely on a single future scenario, but instead calculates thousands of possible futures. ‘The figures and assumptions you insert in your model remain uncertain. But this approach allows us to show which investment choices will continue to work even if things turn out differently than currently expected.’

Starreveld also designed a new algorithm – ROBIST – which helps the model to ‘learn’ along the way, allowing it to become more realistic without the calculations becoming unfeasibly difficult.

Use on the Dutch hydrogen chain

Starreveld applied his methodology to an industrial area in the southwest of the Netherlands, which includes a refinery, a chemical plant and a fertiliser producer. ‘These companies use a lot of energy and are difficult to make sustainable with sources like solar and wind because they require a constant supply of energy and heat.’

Hydrogen could certainly be part of the solution. But there are other options, too, such as electrification and carbon capture. The questions are: which investments are most sensible and when they should be made?

By considering thousands of scenarios, Starreveld's model produces much more robust investment advice than when considering a single future scenario: ‘When making investment decisions, you always have to think ahead. But when unexpected setbacks occur – for example, demand for hydrogen is lower than anticipated – this solution performs better.’

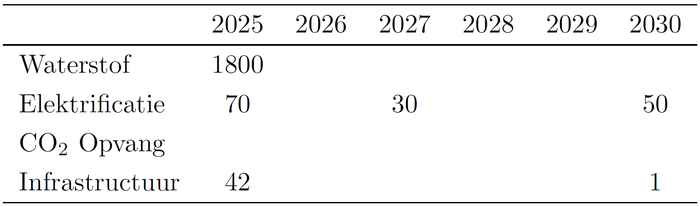

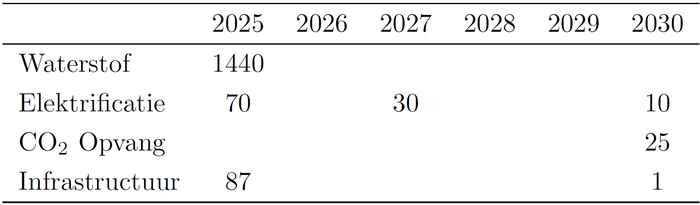

The tables provide an overview for the coming 5 years of the total capital expenditures (in millions of euros) recommended by the mathematical model . The ‘initial’ solution on the left was obtained by optimising for a single future scenario, while the more robust solution on the right takes into account multiple possible scenarios.

From a single optimal solution to a range of smart choices

Starreveld concludes that traditional planning with a single "optimal" outcome is often vulnerable to poor decisions. ‘What seems best on paper can fail in practice if reality proves uncooperative. Consider, for example, the unexpectedly high gas prices resulting from the coronavirus crisis and the war in Ukraine.’

He therefore advocates working with multiple "near-optimal" options. ‘Policymakers and companies can then choose where to invest based on additional considerations, such as public support, spatial impact or political developments.’

More versatile than just hydrogen

Although questions about hydrogen were the primary focus of his research, Starreveld believes the method has broader applications. ‘It could also help in other major societal areas with significant uncertainty, such as healthcare or defence.’

Defence details

Justin Starreveld, 2026, 'Mathematical Optimization Under Uncertainty With Applications to Hydrogen Deployment in the Netherlands'. Supervisors: Prof. D. den Hertog and Prof. Z. Lukszo.

Time and location

Thursday, 29 January, 13.00-14.30, Agnietenkapel, Amsterdam