Leave fossil fuels in the ground now

New insights underline urgency and justice

3 December 2025

Within three years, the world will have used up its remaining CO₂ budget for keeping global warming at a liveable level. ‘This budget represents the limited amount of CO₂ we can still emit before temperatures rise beyond 1.5°C,’ Gupta explains. ‘To avoid catastrophic warming and further damage to people and nature, we must stop extracting and burning fossil fuels as quickly as possible.’

Over the past five years, Gupta and her team examined the role of various stakeholders in the phase-out of fossil fuels and how to ensure fairness in the process. ‘Climate change and phasing out fossil fuels do not affect everyone equally.’

Breaking powerful structures

According to the research team, the fossil fuel sector is supported by a complex web of political, legal and economic structures that reinforce dependence on fossil fuels. ‘Fossil fuel subsidies, trade agreements that allow companies to seek compensation, and the influence of fossil lobbyists in decision-making all slow down the transition,’ says Gupta.

Large amounts of international finance from banks, investors and governments still flow into fossil projects in the Global SouthProfessor Joyeeta Gupta

She points out that fossil fuels are only explicitly mentioned in international climate agreements since 2021, and that at the most recent climate summit there was one fossil fuel lobbyist for every 25 participants. ‘This shows how deeply embedded fossil interests are. We need to break these power structures to enable a shift to sustainable energy systems.’

Delay strategies

But many countries continue to rely on strategies that maintain the central role of fossil fuels in the energy system. ‘For example, some plans allow temporary overshoot of the safe temperature threshold, assuming we can later cool the planet by removing CO₂ from the atmosphere,’ Gupta explains. ‘But the damage to ecosystems, food security and health caused during such an overshoot cannot be reversed. And it is highly uncertain whether these technical solutions will work at scale.’

Another example is the practice of balancing greenhouse gas emissions against the amount countries expect to remove through measures such as afforestation or carbon capture. ‘In practice, emissions then continue unabated, and real reductions are postponed.’

The Interactive Atlas and Stranded Assets index

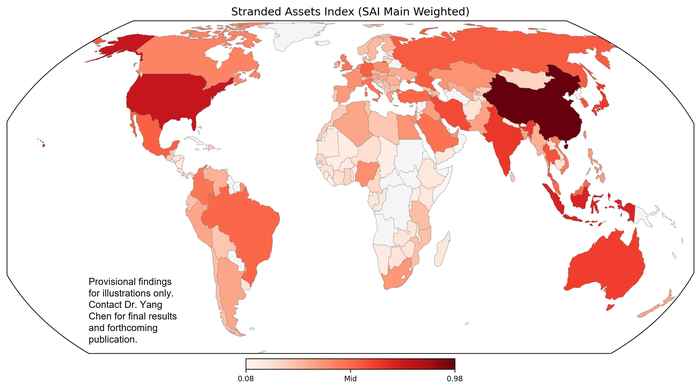

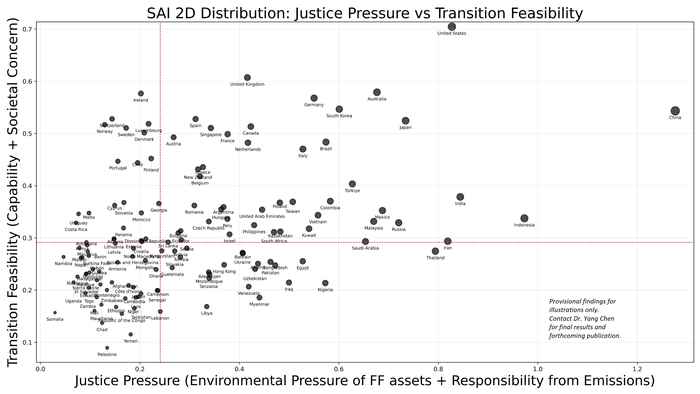

The team developed two tools to support the phase-out of fossil fuels: the Interactive Atlas and the Stranded Assets Index. ‘The atlas maps the various dimensions of the fossil fuel industry,’ Gupta explains. ‘It shows how fossil fuels are produced and consumed, and the financial flows involved.’

The Stranded Asset Index highlights the risks of stranded assets and resources for countries and regions. ‘Imagine a country with large gas fields where the infrastructure has already been built, but where demand for gas will drop sharply in the future due to stricter climate policies,’ Gupta says. ‘Pipelines, installations and even the gas in the ground would then lose their economic value. The Stranded Asset Index shows how large this loss could be and which sectors and regions would be affected. This helps determine how the damage can be distributed fairly.’

Climate justice

Without a fair distribution of costs and benefits, a fossil-free future will remain out of reach, the team stresses. ‘Large amounts of international finance from banks, investors and governments still flow into fossil projects in the Global South. Think of oil fields, gas installations and coal mines,’ Gupta notes. ‘As a result, these countries are locked into fossil fuel exports and the debts they must repay. At the same time, they receive far less investment for renewable energy and green industries.’

A growing counterforce

Nevertheless, the team observes increasing pressure on states and companies. ‘International courts increasingly emphasise that countries are legally obliged to meet their climate targets, and that expanding fossil fuel infrastructure may violate international law,’ Gupta says. Civil society movements and scientists worldwide are also mobilising against fossil fuel expansion, while new initiatives, such as global agreements on energy taxation, are gaining traction.

We need new horizons

Finally, the team concludes that in addition to concrete actions, new horizons are needed. ‘Fossil interests often dominate public debate with stories about economic risks, job losses or the idea that we cannot yet live without fossil fuels,’ Gupta explains. ‘To build broad support for change, we need compelling alternative narratives – stories that show a just, safe and fossil-free future is not only possible, but desirable.’

The research was funded by the European Research Council (ERC) and concluded with the Climate Change and Fossil Fuels (CLIFF) conference at the University of Amsterdam from 25–29 November. Nearly 300 scientists, civil society organisations, policymakers and business representatives gathered at this event to discuss the phase-out of fossil fuels. Go the website of the CLIFF-project