Categorisation of refugees leads to new inequalities

25 May 2021

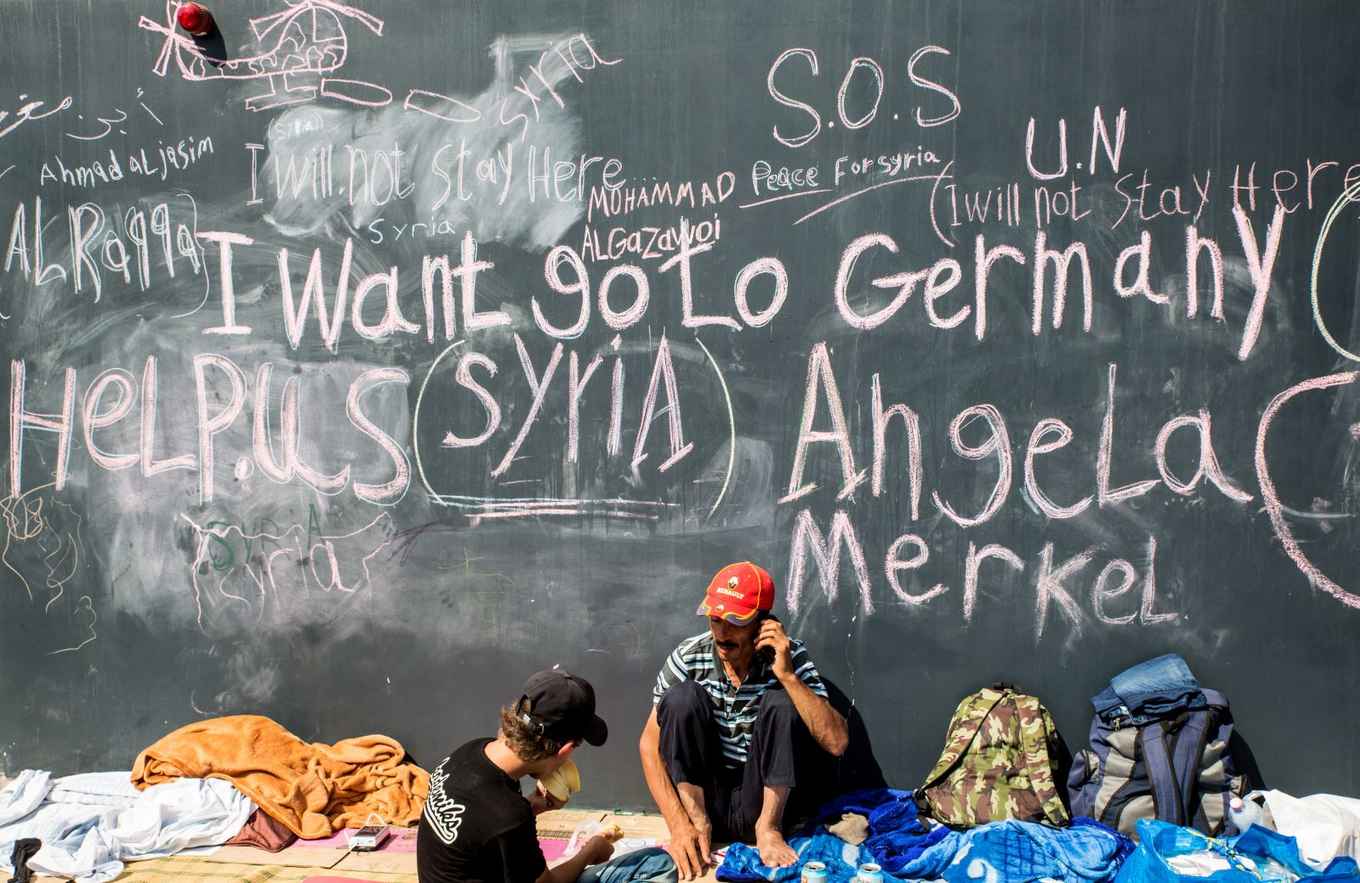

Citing a crisis and scarce resources, European states are increasingly closing their doors and admitting only a limited number of ‘particularly vulnerable’ refugees via resettlement and other refugee admission programmes. Categorisation plays an important role in this admission process, separating refugees into those who deserve help and those who are labelled as undesirable or a risk.

These categories reduce very diverse groups of people to characteristics they supposedly share, such as ‘refugee women at risk’. Other similarities and differences between and within groups are thus ignored, causing one refugee to end up in a relatively privileged position compared to others. This led political scientist Natalie Welfens to take a closer look at the practice of categorising refugees.

Examining the entire admission chain

The main question for Welfens was how categorisation affects the implementation of humanitarian admission programmes and the inclusion and exclusion of refugees. She specifically studied humanitarian programmes to Germany for refugees from Lebanon and Turkey. Welfens looked at what she coins the ‘admission chain’: the sequence of practices that transform people from countries of origin into resettled refugees with legal residence in arrival countries. She tracked how categories were formulated throughout this entire chain: from policy formulation in Germany, through refugee selection, to reception in German federated states and municipalities.

Selection at the frontline

Welfens shows how the selection of refugees works at the frontline. She observes how NGOs, the UNHCR and Turkish state authorities select refugees for admission programmes, and how German state authorities make decisions on admission to their humanitarian programmes. She reveals that humanitarian and security-related principles play a role in these frontline assessments. For example, women, children, sexual minorities, ‘economically vulnerable families, and people with medical needs are considered eligible for selection on the basis of humanitarian needs. But young, heterosexual, able-bodied men and ‘incomplete’ or ‘culturally different’ families are considered risky in the selection process for security reasons.

Justifications for categorisation

Welfens concludes that there are three types of justifications that the different actors in the admission chain use for their categorisation practices:

- Humanitarian justifications that determine who is (most) in need of protection, care or assistance, and prioritise based on people’s needs and vulnerabilities.

- Security-related justifications for determining who is least likely to pose a threat to public, economic and cultural security, and who requires the least integration.

- Efficiency-related justifications that determine admission based on whether it is worthwhile and can be an uninterrupted process.

An in-depth understanding of admission programmes

With her research, Welfens reveals how categories are translated and transferred from one institutional context to another, who gets priority at different steps in the process, and how actors in the process justify this. Welfens thus provides us with an in-depth understanding of how refugee admission programmes work as a policy instrument, and presents a detailed picture of policy categories in admission programmes. She highlights their ability to include, exclude and privilege certain refugees, creating new inequalities where nationality, gender, age and education intersect.

PhD thesis details

Natalie Welfens, ‘Categories on the Move. Governing Refugees in Transnational Admission Programmes to Germany’. Thesis supervisors: Dr Liza Mügge and Prof. Marieke de Goede.

Time and location thesis defence

Wednesday, 9 June 2021, 11:00, Aula, University of Amsterdam