How much transfer time should I plan?

1 July 2024

In public transport you can easily build up a buffer by, for example, leaving home earlier. This becomes a more complicated problem for companies that want to ensure that the entire chain, with many 'switches', of their production process continues to run, especially if they do not know exactly what happens to suppliers who may be abroad. How big should your buffer be?

In recent years, the "just-in-time" model has become increasingly popular for logistics chains. Storing supplies and keeping them in usable condition for producing something is a costly affair. However, keeping buffers small, not only in physical stocks but also in time, makes the process very sensitive to unexpected delays: a transverse container ship in an important but narrow artery for shipping transport, for example. Sometimes even very small, seemingly innocuous delays can lead to a huge cascade of delays throughout an entire system, as sometimes happens with train traffic.

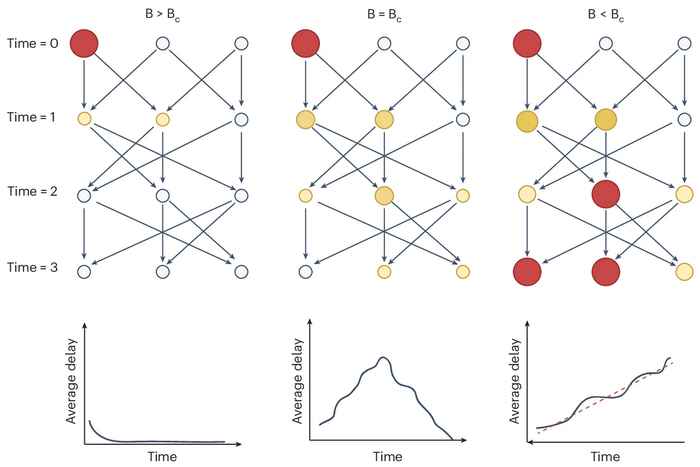

This recent research, published in Nature Physics, into complex logistics networks shows that time buffers cannot be made smaller and smaller with impunity. At a certain, finite, minimum time delay, the entire system goes through a phase transition: it goes from a fluid system to something that is completely 'solid'. The physics of phase transitions, applied to this problem, shows that even just above that limit, a system becomes extremely vulnerable to even small perturbations. There are empirical indications that this plays a role in train route movements in various countries and in international aviation. It can even, through production networks, be a cause of excess variation in countries' GDPs.