Optimizing porous thin films for sunlight-powered hydrogen production

Hydrogen is emerging as one of the most promising sustainable energy sources. The cleanest method of producing hydrogen is through the electrolysis of water using renewable energy. Currently, this process is performed in two separate steps: generating electricity and using electricity for electrolysis. Integrating these processes could vastly improve the production efficiency of hydrogen.

In this project of the MMD TechHub, scientists are working on optimizing electrode materials based on metal organic frameworks to directly convert sunlight and water into hydrogen. This project is led by Sonja Pullen and Bettina Baumgartner, both Assistant Professor in Homogeneous Catalysis, and Emilia Olsson, Assistant Professor at the Institute of Physics and group leader at ARCNL.

Metal organic frameworks

Metal organic frameworks (MOFs) are materials composed of metal building blocks and organic molecules, which can act as a catalyst and convert small molecules into useful chemicals. The benefit of using MOFs is that they can be prepared in a modular way, which enables the design of tailor-made materials.

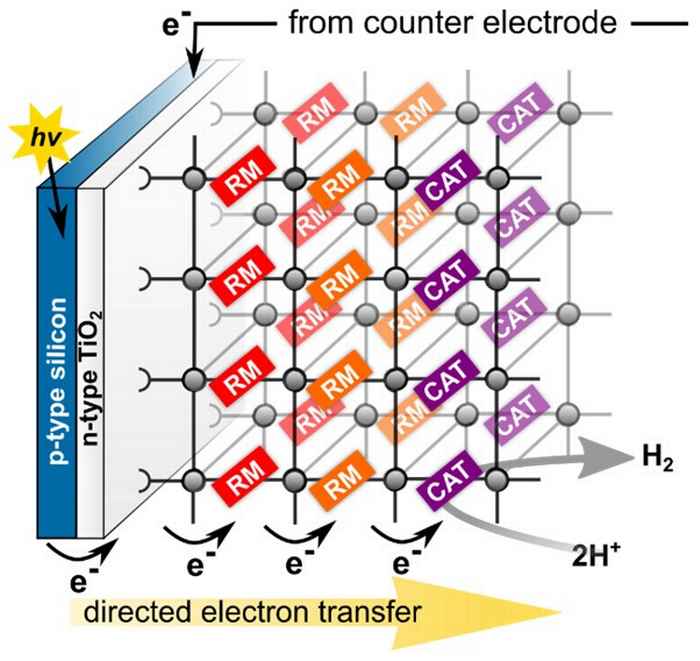

Sonja Pullen, who has over ten years of experience working with MOFs, explains: ‘We want to synthesize these MOFs, immobilize them on an electrode, and apply a potential to establish a high concentration of electrons at the electrode. The goal is that these electrons are transferred via redox mediators (RM in Figure below) to the catalyst (cat), which uses the electrons to reduce protons and produce molecular hydrogen.’

However, the electron transfer across the film is dependent on the hierarchical orientation of different building blocks and structural defects in the MOFs. Pullen: ‘That is why I teamed up with Bettina and Emilia, because they can provide us with very detailed insight into the structure.’

Material optimization

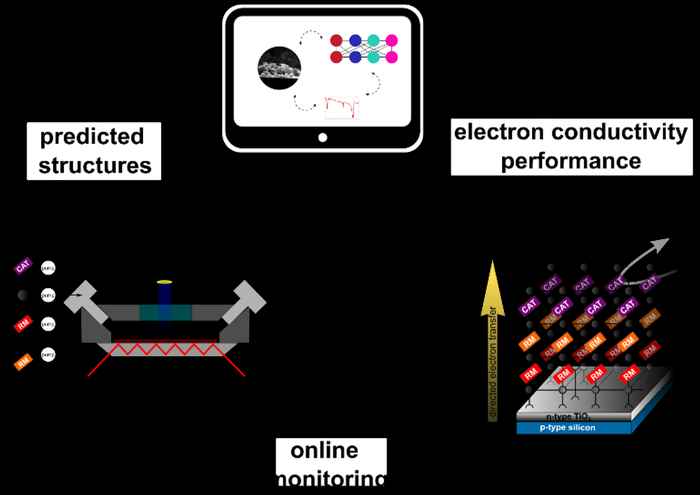

In the project, Baumgartner, whose research focuses on optical setups design and spectroscopy, will optimize a flow cell where the MOFs can be synthesized layer by layer and monitor their growth using spectroscopy. This new synthesis method is significantly more selective and organized compared to traditional methods of making MOFs.

After synthesizing the MOFs and obtaining structural information, Olsson, whose research focuses on atomic scale materials design, will develop computational models based on the experimental data. These models will provide insight into how defects and variations in the film's compositions affect its properties. Olsson will also use AI to predict how they need to optimize the synthesis procedures to improve the MOFs.

Pullen states: ‘Ideally, we establish a loop where we, cycle by cycle, optimize our materials and ultimately produce better catalysts.’

Combining disciplines

Combining computational models with experimental data is not straightforward but very important, according to Olsson. A unique challenge for her is that she has never worked with MOFs before. Olsson remarks: ‘Working with these complex structures, which are different from the carbons and ceramics that we are used to, and coupling organic molecules and metal building blocks within our modeling is going to be challenging but exciting.’

The diverse and complementary backgrounds of the scientists are crucial for this research. Pullen: ‘I'm very excited to work together with Emilia and Bettina. Our combined approach will allow us to move our research into MOFs forward. The theoretical framework that we develop in this project will provide guidelines for designing improved MOF-based electrode materials.’